This is one in a series of profiles on famous people who overcame incredible obstacles, failed many times or defied grim odds in order to succeed.

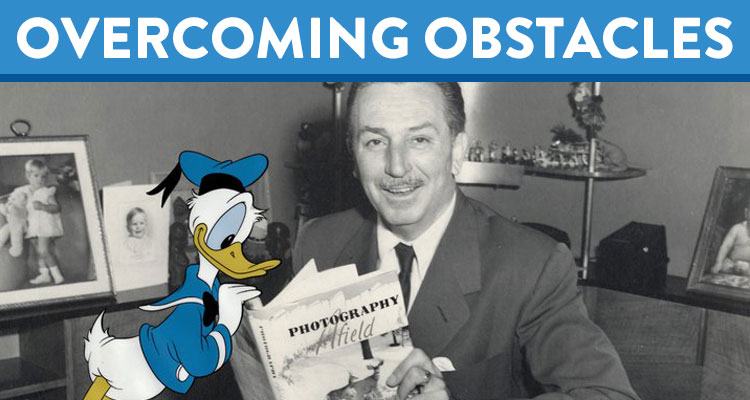

There are few who have had as enormous an impact on our culture and entertainment as Walt Disney. As co-creator of Mickey Mouse he helped to create the most popular and well-known cartoon character in the world. As the founder of Walt Disney Studios, he was an artist who changed animation and film-making forever and has been delighting and inspiring audiences for nearly 100 years. And, of course, when he brought us Disneyland he created a place unlike any other, one that still thrills the imaginations of children and adults today.

But the road to this kind of success and influence wasn’t easy, and it couldn’t have happened without Disney’s ceaseless hard work and unwavering belief in his dreams. Disney faced numerous obstacles—he was put to work at just nine years old, had only an eighth-grade education and almost no formal training in art, and suffered multiple business setbacks. However, he saw these not as failings but as the things that helped to make him the great visionary and businessman he became.

An Entrepreneurial Spirit

According to Michael Barrier’s biography, The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, Walt Disney by Neil Gabler, and other sources:

Walter Elias Disney was born in Chicago, Illinois, on December 5, 1901, the fourth of Elias and Flora Call Disney’s five children. The Disney family was ambitious and entrepreneurial, if not always successful, traits that Walt would inherit. His great-grandfather, Arundel Elias Disney, had emigrated from Ireland to Ontario, Canada. His grandfather, Kepple Disney, left his wife and children to join an oil crew, but ultimately failed to strike oil. Later, Kepple and 18-year-old Elias Disney, Walt’s father, set out for the Gold Rush in California, but made it only as far as Kansas before settling. The family later moved to Florida, where Elias married Flora Call. He purchased an orange grove, only to have a freeze kill the entire crop. According to relatives, “Elias was very much like his father; he couldn’t be contented very long in any one place.”

Elias’ restlessness took him next to Chicago, where he worked as a carpenter, earning a dollar a day. Seeking a safer environment than the family’s rough neighborhood, he purchased a farm and moved the family to the small, but busy railroad town of Marceline, Missouri, in 1906. Walt and Roy, the two younger Disney boys, would later express fond memories of growing up on this “very cute, sweet little farm,” surrounded by orchards and animals, as well as for the bustling little town.

For the first years of his life, Walt enjoyed “leisure time” on the farm, and often visited his “pals,” “Doc” Sherwood and “Grandpa” Taylor, two neighbors in their 70s. Along with his grandmother and aunt, these men were among the first to encourage Walt’s artistic abilities. In 1908, a school opened in Marceline, but Walt wouldn’t begin to attend until 1909, when, at eight years old, he and his six-year-old sister Ruth started school together.

But idyllic life on the farm would soon come to an end. In 1910, Elias became ill with typhoid fever and pneumonia, and subsequently sold the farm. The family moved into town, then to Kansas City, where Walt, despite having already completed second grade in Marceline, was forced to take the grade over. It was here too, that at nine years old, Walt’s free time came to an end.

No ‘Knack for Business’

In 1911, Elias purchased a Kansas City Star delivery route, and Walt and Roy were put to work. Morning, afternoon, and weekends, Elias, Walt and Roy would make their deliveries.

Of this time, Walt would later remember: “When I was nine, my brother Roy and I were already businessmen. We had a newspaper route…delivering papers in a residence (sic) area every morning and evening of the year, rain, shine, or snow. We got up at 4:30 a.m., worked until the school bell rang and did the same thing again from four o’clock in the afternoon until supper time. Often I dozed at my desk, and my report card told the story.” If you’ve seen the film Saving Mr. Banks, you might remember Disney, played by Tom Hanks, reflecting on this period.

Walt continued to deliver papers for Elias for six more years. As the route grew, Elias hired other boys to help, paying them a few dollars a week, but refused to pay his son, insisting it was part of his job as a member of the family. So Walt, already a young entrepreneur, began looking for ways to make his own money, first by making deliveries for a local drugstore while on his regular route, later by ordering extra papers to sell himself, behind Elias’ back.

At ten, Walt opened a stand selling soda one summer with a neighbor boy, but “drank up all the profits.” Later he drew caricatures of customers for a local barber in exchange for free haircuts. While in Kansas City, he also took children’s art classes for “two winters, three nights a week” from the Fine Arts Institute.

In 1917, Walt and his sister, Ruth, graduated from the seventh grade. Shortly after, Elias, who had sold the paper route a few months prior, moved with Flora and Ruth to Chicago to work for a jelly company he had invested in. Walt stayed behind, working for the new owner of the route and living with his older brothers. Not yet 16, he lied about his age and began working alongside his brother Roy as a “news butcher” selling concessions on the trains that passed through Kansas City.

On his own for the first time, he admitted he didn’t fare well. Customers and coworkers alike played jokes on him. Not having learned from the soda stand experience, he often ate the candy bars he was supposed to be selling and by the time summer ended he was in debt to his employer. Years later, Roy said that “he’d come in and he couldn’t account for all that merchandise he took out so he’d run into a loss and who do you think paid his losses?… He was always that way. He never had any knack for business.”

At the end of the summer, Walt joined his parents in Chicago and enrolled in the eighth grade, taking art classes three nights a week at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts and contributing cartoons to the high school’s monthly magazine. Aside from his childhood art classes, this was his only formal art instruction. He worked a variety of jobs, at the factory his father was part owner of, and at the Chicago post office as a mail sorter and substitute carrier, a job he again landed by lying about his age. Always a hard worker, he would seek out more work at the post office after his shift ended, before heading to another job loading trains.

Hoping to join the Army, he dropped out of school at 16. He was rejected, so instead he (again) lied about his age in order to join the American Ambulance Corps. But after falling ill for weeks during the Great Flu epidemic, he didn’t land in France until after World War I had ended, though he stayed for a year as an ambulance driver before returning to Chicago in 1919.

A Self-Taught Artist

While in France he earned money drawing cartoons and caricatures for the men he served with, and drew and submitted cartoons to humor magazines, though all were rejected. Upon returning to the United States he landed a job as an apprentice at a commercial art studio, based on the samples he’d drawn in France, but the job lasted less than a month before he was laid off. Undeterred, he began working on samples and went into business for himself, founding a company called Iwerks-Disney with Ub Iwerks, a colleague who had also been laid off. Shortly after, he left for a job as an animator for Kansas City Film Ad Company, which produced short advertisements for movie theaters.

Animation intrigued Disney, so he set out to learn more. “I gained my first information on animation from a book, which I procured from the Kansas City Public Library,” he said. Gradually, Disney made improvements at the company based on what he had learned. Eventually he convinced his boss to let him borrow an old camera so he could experiment at home, setting up shop in his father’s garage.

He continued to learn and experiment late at night after work and began to make his first films. He named his first film Newman Laugh-O-grams, after a local theater. He took the reel to Newman Theatre in an effort to sell his films, but was so nervous about his first meeting with the theater manager that when asked about the cost of the reel, he blurted out his own costs and ended up making films for the theater at no profit.

Still, he continued working at night, producing one Laugh-O-gram a week while working his day job. Eventually he saved enough to buy a camera and rent a studio. His shop grew, and he produced several longer films but was unable to keep the company afloat. Laugh-O-gram Films went bankrupt in 1923 and at 21, Disney left for Southern California with $40 in his pocket.

A Move to Hollywood

Unable to find the work he wanted as a director, he soon founded Disney Bros. Studio in Hollywood along with his brother, Roy. After some success, and more setbacks, Disney—working again with cartoonist Ub Iwerks who adapted his initial sketches—developed the character of Mickey Mouse (then called Mortimer) and began producing the first Mickey cartoons. After failing to find a distributor for the first two films, they added sound to the third, Steamboat Willie, found a distributor and before long Mickey Mouse surpassed Felix the Cat to become the world’s most popular cartoon character.

Disney had success with Mickey and his two subsequent cartoon series, receiving his first Academy Award. But he had bigger plans for the newly renamed and expanded Walt Disney Studios. He began work on a full-length animated feature film based on the fairy tale “Snow White;” a move dubbed “Disney’s Folly” by those in the film industry who were convinced it would destroy the company.

His wife, Lillian, and brother, Roy both tried to talk him out of it but Disney pushed forward with the project. He experimented with realistic animation, developed special effects and new processes and techniques all in pursuit of a film that would meet with his expectations. Production started on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1934 and continued for three years before the studio ran out of money. Disney was able to get a loan to finish the film by screening a rough cut, and the film was finally released in February 1938. It became the most successful film of the year and earned $8 million, the equivalent of about $134,033,100 today.

Snow White launched what would be known as Disney’s “Golden Age,” winning him a full size Oscar and seven miniature ones, and allowed him to build a new studio in Burbank, California. The new studio opened in late 1939, with animation staff already hard at work on Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi, Alice in Wonderland, and Peter Pan and work continuing on cartoon series featuring Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, and Pluto.

In the late 1940s, Disney began working on ideas for a children’s theme park, an idea he would spend the next five years developing. When funding proved difficult to find, he found new ways of fundraising, broadcasting a show called Disneyland on a then-new network called ABC in return for help financing the park. In 1955, he finally opened Disneyland, and dedicated the park on live television saying:

“To all who come to this happy place; welcome. Disneyland is your land. Here age relives fond memories of the past … and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future. Disneyland is dedicated to the ideals, the dreams and the hard facts that have created America … with the hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world.”

What we can learn from Walt Disney

On learning and education:

Disney’s formal education ended in the eighth grade, and his education up to that point was often interrupted. Some have suggested that the many jobs Disney held and his struggle in school was due to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and he is often included on lists of famous people with ADHD. However, there’s little credible evidence to suggest that this is true. It’s more likely that his poor performance in school was due to being forced to needlessly repeat a grade, being pulled out to work, and being so tired from working for his father that he often fell asleep in class.

Despite his lack of formal education, Disney never stopped learning: reading, teaching himself animation, tirelessly experimenting and working to improve his craft. He showed that it’s possible to be successful despite following a different path from the expected one, or through alternatives to college, like the apprenticeship he took.

But he knew, too, the value of learning from others’ expertise saying:

“All you’ve got to do is own up to your ignorance honestly, and you’ll find people who are eager to fill your head with information.”

On the value of hard work:

“Do a good job. You don’t have to worry about the money; it will take care of itself. Just do your best work — then try to trump it.”

Of his time as a young boy, working the paper route he said: “I don’t regret having worked like I’ve worked…I can’t even remember that it ever bothered me. I mean, I have no recollection of ever being unhappy in my life. I look back and I worked from way back there and I was happy all the time. I was excited. I was doing things.”

On failure and adversity:

Of the failure of Laugh-O-grams he said: “I failed… I think it’s important to have a good hard failure when you’re young… I learned a lot out of that.”

“All the adversity I’ve had in my life, all my troubles and obstacles, have strengthened me. … You may not realize it when it happens, but a kick in the teeth may be the best thing in the world for you.”

On setting goals:

“A person should set his goals as early as he can and devote all his energy and talent to getting there. With enough effort, he may achieve it. Or he may find something that is even more rewarding. But in the end, no matter what the outcome, he will know he has been alive.”

On books and reading:

“There is more treasure in books than in all the pirates’ loot on Treasure Island and at the bottom of the Spanish Main… and best of all, you can enjoy these riches every day of your life.”

On curiosity:

“Around here… we don’t look backwards for very long. We keep moving forward, opening up new doors and doing new things, because we’re curious… and curiosity keeps leading us down new paths.”

On having big dreams:

“To the youngsters of today, I say believe in the future, the world is getting better; there still is plenty of opportunity. Why, would you believe it, when I was a kid I thought it was already too late for me to make good at anything.”

“It’s kind of fun to do the impossible.”

Walt Disney’s life and work show the value of imagination and dreaming big. But he also showed us that it’s not enough to have big dreams. Hard work and persistence were the keys to overcoming the obstacles in his path, as they are for so many others who have overcome even the most seemingly insurmountable odds.

Image © Disney, Quotes via Wikiquote, The Animated Man