In July, a group of healthcare professionals achieved an outstanding medical triumph. Eight-year-old Zion Harvey underwent an 11-hour operation at The Children’s Hospital in Philadelphia to receive the first pediatric dual-hand transplant ever. Ten surgeons, on a team of 40 specialists, worked bone to bone, artery to artery, nerve to nerve, and tendon to tendon—an effort of astounding proportions. Looking at Zion, who appeared on national television after the successful transplant, makes you proud to be a human being. Hey, we did this! And what better way for kids to learn the impact that science has in real life.

I’m old enough to remember the first heart transplant. A woman named Denise Darvall was in a car accident in South Africa in 1967 and was declared brain dead. Louis Washkansky, a man in his 50s, was going to die without a heart. A cardiac surgeon and his team were ready. Washkansky received Darvall’s heart. The transplant was successful, but Washkansky died 18 days later from an immune reaction. Still, the surgeon, Christiaan Barnard, was considered a hero throughout the world. Pioneers before him, like surgeon Norman Shumway, had paved the way with scientific and medical studies on heart transplantation. To me, what seems most odd (and almost funny) is that heart transplants are routine today. More than 3,500 were performed last year. Heart transplants are almost unbelievable, and yet nobody gives them a second thought.

Here’s one more example before I make my point. In February of this year, at Texas Children’s Hospital, two ten-month-old conjoined twin girls were surgically separated. They shared their liver, the lining of their heart, their colon, and their pelvis—yet a group of skilled surgeons successfully separated them. Two other sets of conjoined twins were separated in Houston hospitals in the 1990s. I read a line on one website about them that is as monumental as it is simple. The line read, “All four children are still alive.” Make that six. Six kids get a chance at normal lives. Take a look at these two girls—don’t you feel happy for them? I do.

I’m a man with a scientific bent, and yet I would not hesitate to use the words miraculous and heaven-sent when describing these and other breathtaking achievements. I’ve even experienced my own version of a medical miracle after undergoing a serious surgery and enjoying an unusually rapid recovery.

But, I am also rational enough to remember that William Harvey wrote De Motu Cordis in 1628, describing how blood circulates in the body. Every doctor and nurse who transplanted those hands and heart or separated those conjoined twins didn’t have to think twice about how blood circulates—scientists and doctors worked it out long ago, so miracles can be done now.

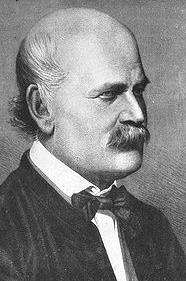

via britannica.com

The most ill-fated physician of all, Ignaz Semmelweis (the “savior of mothers”), was driven insane by the response to his call for doctors to wash their hands before delivering babies in order to prevent infection (his call was ignored, and he was rejected and ridiculed). Eventually, he was committed to a mental institution where he was beaten by guards and died, ironically, of an infection. But mothers are now safer by light years and, today, the name Semmelweis stands for all that is decent in the human spirit. Our understanding of germs and bacterial science had to wait just a bit until scientific giants Pasteur, Koch, and Lister taught us the facts about germs. But now we know, and doctors wash their hands before getting down to the business of being miracle workers. In fact, we all recognize the importance of hand washing to prevent infection.

via semmelweis.org

My point is this: science and medicine fit together like a hand and glove. Science asks questions about the very fundamental aspects of biology (or matter, or the universe): How does blood flow? What causes disease? Doctors, nurses, and engineers take this fundamental knowledge and use it to create and to take risks based on facts. A boy in Philadelphia has two hands now, six children who stopped by Houston are now living normal lives, and countless patients have undergone life-saving heart transplants. All are testaments to human medical skill and dedication—but all these miracles rest on the hard work of scientists who uncovered the fundamental underpinnings of how the world around us works.